As fraternal twins and collaborating artists, it is immediately evident how connected Nikolai and Simon are both personally and professionally, literally finishing each other's sentences during the interview. Their dynamic painted a vivid picture of their unique and deep relationship as siblings and artists; their comfortable rapport not only highlighted their whimsical style, but also their distinctive approach to artmaking where each brother’s input is both individual and complementary.

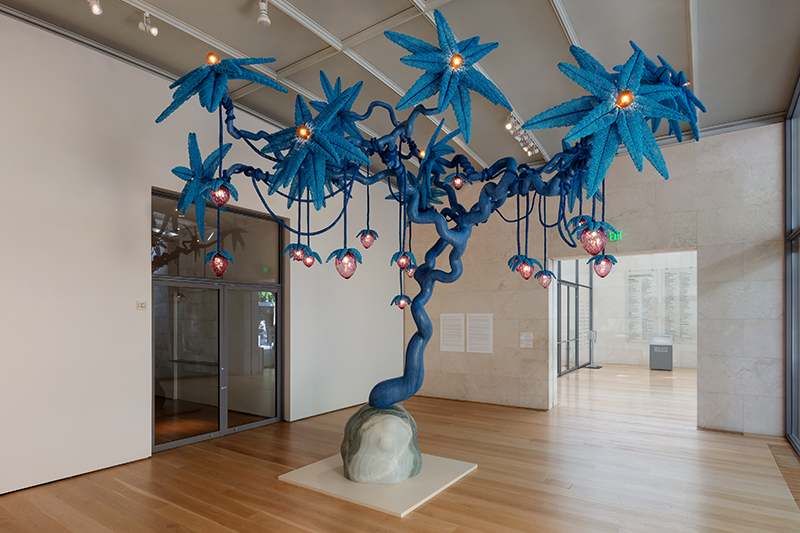

Haas Brothers: Moonlight showcases fantastical sculptures that highlight the artists’ distinctive fusion of art, design, and technology. In front of the museum, two Moon Towers–inspired by the iconic moonlight towers that lived right outside of the brothers’ childhood home in Austin–greet visitors before they even enter the museum. The tall, glowing sculptures function as streetlamps, recalling both the Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí’s organic architecture and the French designer Hector Guimard’s sinuous art nouveau forms. Inside the museum in the Nasher’s Public Gallery is the whimsical Strawberry Tree, a cast-bronze tree complete with hand-beaded leaves and blown glass strawberries that glow under the foliage. Lastly, in the Nasher’s garden is Emergent Zoidberg, an eight-foot-tall sculpture created from a combination of craft and computation. The sculpture pays homage to Dr. Zoidberg, a central character in Matt Groening’s animated television series “Futurama.” Altogether, the series of dream-like, illuminated works make up Haas Brothers: Moonlight.

Nasher: Can you talk about the references and inspirations from both your upbringing and your experiences as artists that have shaped your work? What elements of pop culture and nostalgia did you incorporate into Moonlight, and how do these memories contribute to your creative process?

Simon Haas: A lot of our imagery and aesthetics comes from Austin. There was the Mangia Pizza dinosaur, which was a big dinosaur on top of a pizza shop. Then there's Conan's Pizza, also a pizza shop.

Nikolai Haas: Yea, they had all these Frank Frazetta-like fantasy art drawings, like Conan the Barbarian. The drawings were on the tables in the shop, women with like huge boobs and swords and dudes that are all ripped, and he's, I mean, I don't even know what...

SH: They're in panties.

NH: Panties, basically, yeah.

SH: And then Eeyore's Birthday Party always happens once a year!

We were also close to Shull Creek, so we could walk down there. Austin was wacky and there were a lot of public sculptures that were signs for places. The first Whole Foods had all these fruits and chickens on top. So, I think our relationship to objects comes from Austin. They're not necessarily serious objects always, but you wind up having a relationship with them. Our stuff is serious, but we like to present it as being super pleasant to look at and not that serious.

NH: You've got like the Butthole Surfers, which were making amazing music in the 90s. Brian Johnson, Nirvana, Kurt Cobain, who wore like a Brian Johnson shirt. It said, "Hi, how are you." MTV culture was blowing up and there's all sorts of weirdness, truly that's when people started saying “Keep Austin Weird.” We joke that that’s our aesthetic, the way that we make things is almost like Austin stoner culture. There is a little bit of humor in it. It's always nice to look at but also a little psychedelic aesthetically. But it's about likening to our childhood. We never really grew up, I guess, in that way.

SH: Yeah, I know. Well yeah, I think I did.

N: The Strawberry Tree is perhaps the most complex piece within your Nasher exhibition. The intricacy of the beading is truly remarkable, yet it can be difficult for many to fully appreciate just by looking at it. Can you talk about what the beading process was like?

SH: I personally love to systematize things and when I start a new material, I need to test as much as I can to understand it. And it turns out with beads, there’s an infinite number of ways to string them together. The systematization process took me five years to figure out, but it’s basically an operating system written for beads.

NH: Simon is working with two units, almost like ones and zeroes in a computer. The software is a short line of code that Simon has written, and the hardware is the human applying it to creating a structure or part. We are really interested in the idea of “emergence” and “emerging properties,” which is the idea of having a very simple rule that has the potential to make something much more complicated if you let it go.

SH: One example of emergence is a cave formation. You have one rule or thing going on, which is like the drop of water coming from some porous hole in a cave. Over a millennium, it’s dropping a little bit of sediment in one spot over and over – that is the one simple rule. And yet the result is these super complicated, unbelievable stalagmite or stalactite formations. Simon has one little rule, telling you when to add or delete beads, but once you run the program, it creates so much more. Everything in this show has some sort of relationship with ideas of emergence.

N: Within art history, beading is often categorized into the Arts and Crafts movement. This movement was an international trend in decorative and fine arts and is often considered the mastery of technique and material. Can you tell us more about the beads and how they were made? And could you elaborate on the historical context of beading in the Arts and Crafts movement and what it means to you as artists?

NH: It's very important to us for craft to keep going.

SH: The beads are special, and each was hand done, which is cool.

NH: When Simon was in Venice, he met this woman who had inherited a bead factory in 1982 and she didn’t have a great relationship with the factory, so she shut it down immediately. We went in 2017 and the factory had vines coming through it and scorpions everywhere. There was no electricity and rain was coming in through the ceiling, but we started opening all these old wooden boxes and inside was just this incredible number of beautiful, antique beads of all different colors. We don’t know exactly how to date them, but they’re all made sometime from the early 1800’s to 1982. The way the beads were made back then is incredible! Today, there’s all sorts of rules and regulations, which should have been in place because people were using all kinds of toxic materials.

SH: One person blows a bubble of glass, and another person sticks his punty into the end of it and they run in opposite directions to make a long bubble. Then they chop it up, so each bead has its own little unique shape.

N: Speaking of craft, the base of the tree is made of stone, correct? There appears to be a common trend in your work, often incorporating traditional craft like beadwork, blacksmithing, bronze casting, and stonework—skills that are incredibly intricate and require years of practice to master. Could you describe your affinity for these crafts and your commitment to keeping these traditional techniques alive in your art?

SH: Stone carving is something that does not happen much, and blacksmithing, very few people do that. Beadwork is thought of as a simple craft and it has not really been taken too seriously. Murano is sort of in a decline because the industry is not there to support the craft and it's starting to be taken less seriously. We feel really drawn to work with that material to keep it alive.

NH: We're designers, we love putting things next to each other and deciding what looks good. We often end up picking materials that are timeless, just because we grew up doing such archaic craft, like stone and metalworking and that kind of stuff.

SH: We're really attracted to materials that have weight and reality to them. This thing, you could see it in five or six years, and it'll be in the exact same shape it's in now.

NH: We are making work that will live into the future.

SH: Niki and I both were stone carvers as kids. I learned at school how to do blacksmithing, so I've always loved metal. And then the beads are something that just came to us later.

NH: Yeah, we were stone carvers in Austin, that’s how we grew up. We worked with this awesome quarry in Portugal called Pelle de Tigre. It’s a beautiful stone and we wanted to include that in this piece.

NH: Also, mixing glass with stone is, sort of materially, poetic, right? Because they’re both silica but they’re completely opposite materials.

SH: We love combining stone and glass because they’re both hard to work with.

NH: A part of making art with these materials is also to try to keep the traditional alive, because these are going to go away at some point. There's going to be people that don't know how to blow glass well.

SH: And you actually can't make beads like this anymore.

N: And the strawberries on the Strawberry Tree are blown glass – how did you come up with the specific strawberry technique? And why a strawberry tree?

NH: We like to skew things just a little bit, so you know that they're not reality, even though they feel so palpably almost real. Like you look at this thing and you go, is that real? It's obviously not. You can't grow strawberries on a tree. That's the point.

SH: We were working at Pilchuck Glass School and there were a lot of artists there from all over the world. We met a glass blower from Japan, and she had an idea for how to make a strawberry, so she was the one who really helped us find this form. It’s a process for blowing the glass into a mold that is kind of star shaped. It’s like a starburst. So, you blow it and then you pull it out and snip it over and over.

NH: And you have this shape that has lines along it and when you snip along the line, you create different deflections that make these little seeds. It’s very physical, almost like working with taffy.

N: Color plays a significant role in your work. Can you talk about how you approach color selection for your installations? Is there a particular meaning or intention behind the colors you chose for Moonlight?

NH: The beads dictated it initially because we loved this color bead.

SH: We were choosing between a few, but this one fits the title Moonlight the best.

NH: The trunk, trees, beads and everything else were about what the work might look like in moonlight. So even if it's during the day, it's a take on a moonlight vibe. We also chose red strawberries because people look great in red light.

SH: And it looks nice against the blue. Another tie to Venice, they have streetlamps that have pink panes of glass in them and it's a really similar color to this. This color means a lot to me in that way.

NH: It's Venetian pink, it can't be made any longer, so this is our imitation. We didn't find antique strawberries just laying around the factory, so we had to make them ourselves.

SH: It's similar though.

NH: Yeah, the same color.

N: Many artists listen to music or have the TV on in the background while they work. It's interesting how these external influences can shape the art and even spark memories later, reminding the artist of the work. During the process of creating Moonlight, was there anything you did—like listening to certain music or watching specific shows—that influenced the exhibition? What kind of music do you typically listen to while working?

NH: I don’t think there’s a genre of music I don’t listen to.

SH: I listen to EDM, specifically Italian EDM.

NH: Simon says I listen to hippie music.

SH: He does.

NH: Not true! I listen to everything. Actually, the name of the exhibition comes from the Claude Debussy song, Clair de lune, which directly translates to “moonlight.” Debussy was inspired by a Paul Verlaine poem that had been written decades earlier and it’s about how being in moonlight makes things strange or unusual or gives you a different perspective. So, Debussy covered that poem using music. And then there’s a beautiful version that we’d found recently by an artist names Isao Tomita who covered the song using synthesizers.

There’s this effective filtration in humans taking the media on, filtering it, changing this one piece of media that started as a poem into these super beautiful and different forms. So, for us, we’re sort of covering the Isao Tomita song in sculpture. And that goes back to the concept of “emergence” and how important that is in our practice.

N: Can you tell us more about how moonlight has been a part of your lives and how it inspired this project outside of the title?

SH: In Austin there are a bunch of moon towers that emulate moonlight. They're high up, and I'm sure many people know we grew up on the corner of Twelfth and Blanco in Austin, and there's a moon tower there. Every time we walked outside of our house there was always moonlight, so we felt very comfortable in it. We would do night hikes and there's a limestone here which glows in the moonlight. You don't need lights or anything. If the moon's out, you can see the whole trail ahead of you, and it's just nostalgic. Moonlight is a nostalgic thing for us.

NH: Conceptually, moonlight is a beautiful way to explain the space in between the shift of perspective, how the viewer interprets a work of art, but also projects it onto themselves. We began as designers and as we started getting pushed into the realm of sculpture, people kept asking us why we are artists now and not designers.

We’re both, that’s the answer. We try to leave room for interpretation and push people to change their perspective about the way they see the world. So, “moonlight” is sort of a more poetic way to explain what art, for us, is all about.

Image Credits:

Images from top to bottom: Strawberry Tree Installation Image by: Kevin Todora, Lucy in Disguise street view shot courtesy of the Haas Brothers, Kevin Todora, Strawberry Tree Installation detail shot, Kevin Todora, Garden Installation Exhibition detail shot, Campus sunset of Pilchuck Glass School: Photo by Stephen Vest, Moontower in Zilker Park on Monday April 15, 2019. Jay Janner/American-Statesman Austin American-Statesman, Kevin Todora, Moontower Installation detail shot